The following is a sample profile from the book Holy Troublemakers & Unconventional Saints by Daneen Akers.

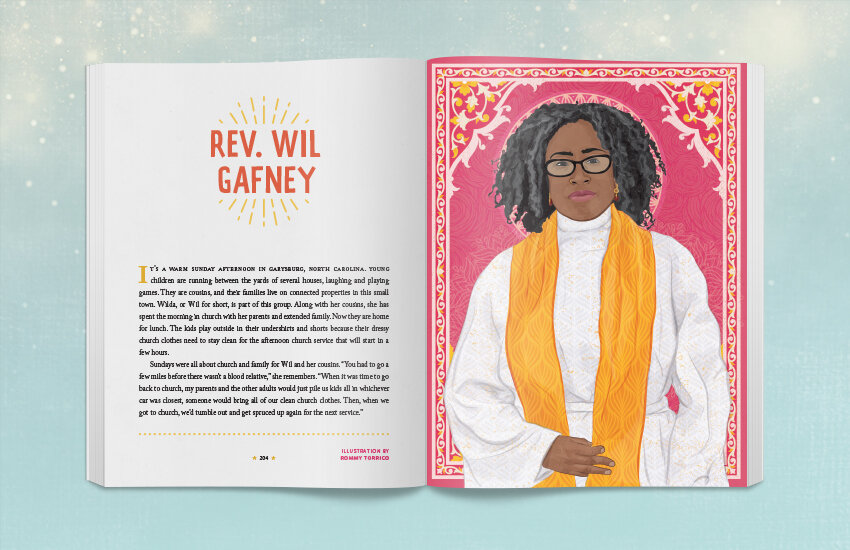

Rev. Wil Gafney

It’s a warm Sunday afternoon in Garysburg, North Carolina. Young children are running between the yards of several houses, laughing and playing games. They are cousins, and their families live on connected properties in this small town. Wilda, or Wil for short, is part of this group. Along with her cousins, she has spent the morning in church with her parents and extended family. Now they are home for lunch. The kids play outside in their undershirts and shorts because their dressy church clothes need to stay clean for the afternoon church service that will start in a few hours.

Sundays were all about church and family for Wil and her cousins. “You had to go a few miles before there wasn’t a blood relative,” she remembers. “When it was time to go back to church, my parents and the other adults would just pile us kids all in whichever car was closest, someone would bring all of our clean church clothes. Then, when we got to church, we’d tumble out and get spruced up again for the next service.”

Illustration by Rommy Torrico

For young Wil, growing up in Black church culture meant memorizing and reciting Bible verses, singing gospel music, going to church summer camp, and participating in church all day on Sundays with her whole family.

Black churches hold the Bible in high regard—sermons are typically built around the Bible, and so Wil grew up knowing the stories and characters of the Bible. This deep knowledge served her well when she eventually came to understand that she was called to teach and preach. She went back to school to get specialized training meant for pastors and priests. As part of her graduate education, she learned Biblical Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and Aramaic. She noticed that many of her White classmates didn’t know the Bible stories and characters nearly as well as she did, and that made translation harder for them. “I could often figure out the grammar of the text simply because I knew the stories so well from growing up in the Black church,” she says.

Now she is a biblical scholar, author, priest, and professor of the Hebrew Scriptures, and her full title is the Rev. Dr. Wil Gafney. She teaches in classrooms, through her books, and online to many thousands of people who have learned to turn to her for insights, translations, and commentary. Rev. Wil is especially known for being a womanist scholar.

To many people, womanism is a new concept. For Rev. Wil, the short definition of womanism is that it is Black feminism with much more to it. Feminists believe that women and men are equal. Because of the culture in which modern feminism was born, however, the main reference points for feminists are often the experiences of White women. Womanism is instead interested in the perspectives of the people in texts who often are overlooked or unheard, usually the voices of women, enslaved people, and children.

“Womanism is interested in the well-being of the entire community, and that especially means the well-being of those who are vulnerable and often exploited,” Rev. Wil explains. “To get there, we start by listening to Black women.” Womanism asks deeper, bolder, and broader questions than feminism has asked and uses the experiences of Black women to interpret texts.

For example, Rev. Wil illustrates what a womanist perspective can bring to the often-quoted phrase, “The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” Those three men are important ancestors of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim faiths, and many details of their lives are listed in the Hebrew Bible. However, Rev. Wil points out that we often do not know the names of the women these three men fathered children with. Some of them were wives, and others were enslaved women forced to have children with these men.

It can be uncomfortable to face the questions that arise when we try to listen to a sacred text through the voices of the women and marginalized people who did not get treated well by people we’ve been taught to admire. But it can give us fresh and new perspectives about the texts.

“I believe in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, but I also believe in the God of Hagar, Sarah, Keturah, Rebekah, Rachel, Leah, Bilhah, and Zilpah,” Rev. Wil says. Not only do the stories of these often-forgotten women teach us, but by naming them, we show them respect.

“Saying a person’s name is very important in African-derived cultures,” Rev. Wil says. “So, it’s important to say their names.”

The names we use for God are another important part of Rev. Wil’s teaching, too. Language matters; the way we speak about God determines what and who we value most. So Rev. Wil asks her students to think about the question: “What is your God language and why?” For example, for many centuries the word “God” has usually been translated in masculine and male terms only. This is not an accurate interpretation of the original texts. “As long as ‘men’ and ‘God’ are in the same category, our work toward equity will not just be incomplete,” Rev. Wil says. “As long as a masculine God remains at the top of the pyramid, nothing else we do matters.”

Even though so much tradition and virtually all of the Biblical texts and books about God have translated “God” as only masculine, that is not how the words and grammar of the original Hebrew text actually describe the Divine. God is both male and female, just like the humans created in the image of God. Rev. Wil’s careful translation of the first two verses of Genesis demonstrate this.

It reads:

“In the beginning, He, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was formless and shapeless and darkness covered the face of the deep, while She, the Spirit of God pulsed over the face of the waters.”

Rev. Wil teaches her students that the word for God’s Spirit in Hebrew is ruach, and it is always a feminine noun. In many languages, nouns have a feminine or masculine gender, but English grammar does not have gendered nouns. Centuries of all-male translators left out the feminine from the language about God by simply removing pronouns. (Pronouns are words we use instead of nouns to avoid sounding repetitive. Common pronouns include “we,” “she,” “him,” and “they.”)

So, whenever the original text says, “The Spirit” in Hebrew, the male translators wrote “God.” The word “God” does not require a masculine pronoun (he/him) or a feminine (she/her) pronoun. However, because most people are so used to associating maleness with God, they still hear the word “God” as masculine. But God is also She. “She, the Spirit of God, She-who-is-also-God, at the dawn of creation fluttered over the nest of her creation at the same time as He, the more familiar expression of divinity, created all,” Rev. Wil writes. “God is female and male, and when God gets around to creating creatures in the Divine image, they will be female and male, as God is.”

Rev. Wil asks her students to imagine hearing scripture with the feminine gender of God’s Spirit still present in the words. Some examples include, “She rested on them,” “The Spirit of God came upon David,” and “She made me.” This last phrase is in the Hebrew Scriptures more than 30 times, usually when describing God’s Spirit urging someone to take action.

Because Rev. Wil goes back to the original languages and finds the feminine grammar that has been overlooked for centuries, she sometimes calls herself a literalist. “Feminine language for God occurs in the text repeatedly. This means that feminists and womanists advocating for inclusive and explicit feminine God-language are not changing but restoring the text and could be considered biblical literalists.”

Rev. Wil helps her students to find names for God that go beyond gender, in addition to the names that are already familiar. “Some people use Holy One, Creator, Sustainer, The Sovereign,” she says. “Fountain of Life is one that comes out of Judaism. I’ve had some students who’ve used the word LOVE in all caps. I let them choose a name that speaks to them.”

What is your favorite word for God?

Note: You can now read a new essay about why we need clearly feminine titles and images for God that includes more of Dr. Rev. Gafney’s scholarship here.

Glossary Terms

Advocacy/Advocate

• An activity that aims to bring about positive change or support for a person, a group of people, or a cause.

• A person who publicly speaks out or otherwise works for the rights of others or to support a cause.

African-derived Cultures

Cultures that originated in Africa with unique art, history, cuisine, music, and more. Today African-derived cultures are present throughout the U.S., the Caribbean, South America, and in other countries where descendants of enslaved people from Africa live.

Black Churches

Protestant churches attended by mostly Black Christians in the U.S. Prior to the Civil War, Black congregations were not allowed by White slave holders in many slave states unless a White minister oversaw the service. Black churches founded by free Blacks in northern states provided shelter, aid, job connections, and often education to formerly enslaved people who had escaped from the South. Later, racial segregation often blocked Black people from White churches, so Black ministers started their own churches. Black churches are central places of community, connection, and safety for many Black Americans.

Called/Calling

The sense that God, or a messenger of God, has specifically assigned a person a certain job; often applied in religious job settings, such as, “I was called to become a minister.”

Christian/Christianity

A person who practices Christianity, the Abrahamic Religion based on the teachings of Jesus, a first-century Jewish teacher. While there are many different types of Christians who vary widely in belief and practice, all find the life and teachings of Jesus to be of central importance.

Culture

The customary beliefs, traditions, art, food, dress, and ideas of a particular people and place.

Equity

Giving everyone what they need to be successful; what people need to be equal will look different based on where each person is coming from.

Feminist/Feminism

A person who works for the social, political, legal, and economic rights of women, believing them to be equal to those of men. Because of the culture in which feminism emerged, it often focused on the experiences and rights of White women (see Womanism).

Gender

A person’s internal sense of being a boy, girl, or somewhere in between.

Hebrew Scriptures

The holy text of Judaism which describes the promise between God and the Jewish people; the Christian Bible uses the same texts but often calls them the “Old Testament,” but for Jews, there is nothing outdated or “old” about these texts.

Jewish/Judaism

A person who follows Judaism, which is likely the world’s oldest monotheistic religion (belief in only one God). Judaism was formed nearly 4,000 years ago by the ancient Hebrews. Jews believe God formed a special covenant with Abraham to form a great nation from his descendants if he followed God’s directions. Judaism is one of the three Abrahamic faiths and emphasizes living a just and compassionate life that respects all people as made in the image of God.

Literalist

A person who follows a text word-for-word; when applied to a religious setting, a person who believes that every word of a holy text is from God and to be strictly followed.

Marginalized

A person or group who is treated as unimportant and not given full respect by the larger society; often granted fewer rights than others.

Muslim

A follower of the religion of Islam.

Womanist/Womanism

A person who practices womanism; Womanism is Black Feminism that listens for the perspectives of the people in texts who often are overlooked or unheard, usually the voices of women, enslaved people, and children.

Read another sample chapter from the Holy Troublemakers & Unconventional Saints book by Daneen Akers.