The following is a sample profile from the book Holy Troublemakers & Unconventional Saints by Daneen Akers.

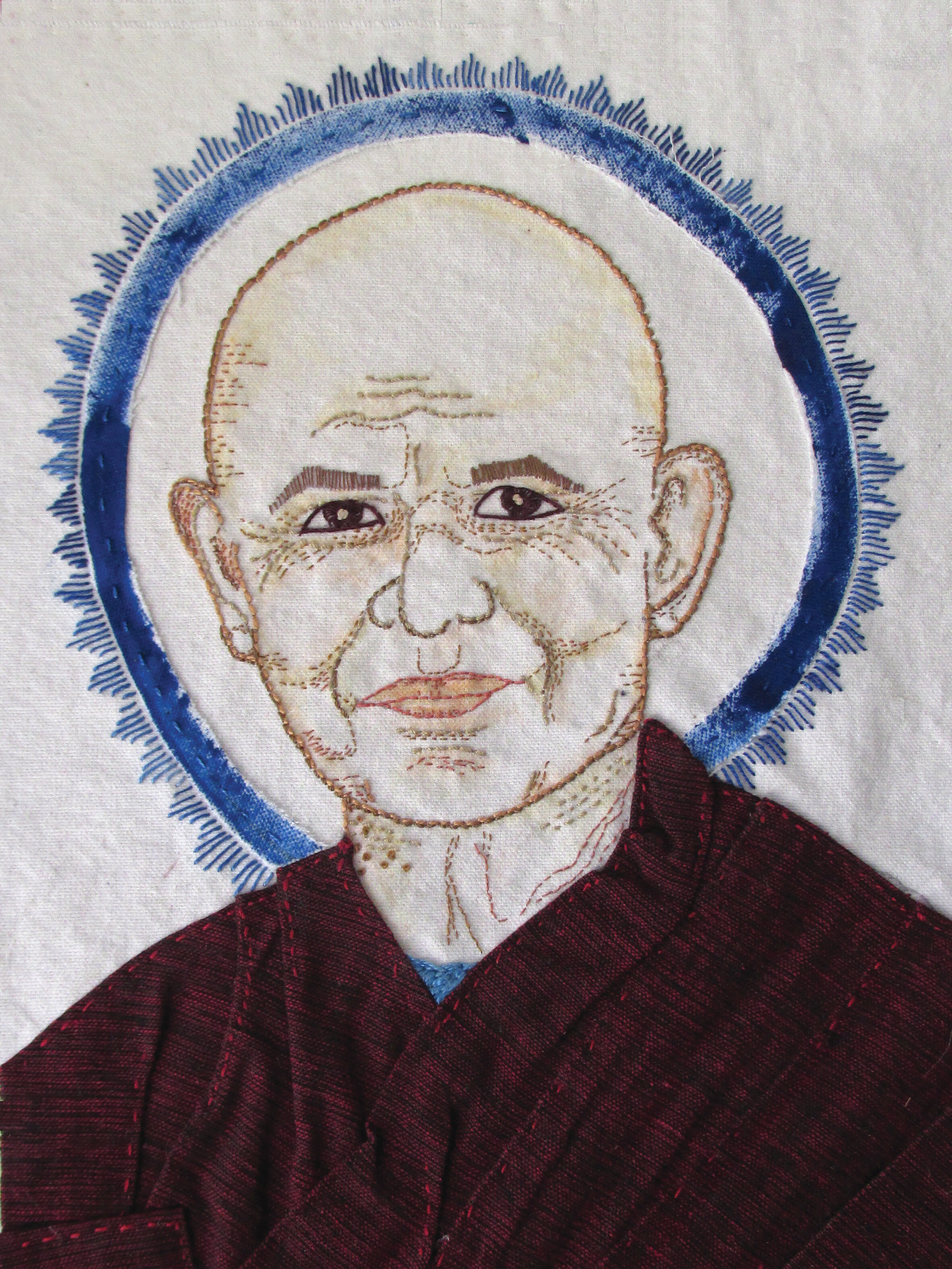

Thich Nhat Hahn

One day in Hue, a city in central Vietnam, a little boy of eight looks through a popular Buddhist magazine, reading bits and pieces of the articles. Flipping a page, he sees the face of Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. He’s seen pictures of Buddha before as Buddhism is one of the main religions in Vietnam. Something about this picture especially captivates this boy. In it, Buddha is sitting on the grass, his serene smile is filled with gratitude. “I want to know that kind of joy and peace,” the boy thinks to himself.

This young boy will grow up to be Thich Nhat Hanh, a committed peace activist and one of the best-known teachers of modern Buddhism. The spark of connection that he felt that day looking at the picture of a smiling Buddha stayed with him, and he convinced his parents that he was serious about wanting to study Buddhism and live as a Buddhist monk. Monks live a life devoted to their faith, usually at a monastery with other monks who are also dedicated to living simple lives and following structured routines and daily tasks. He was ordained as a beginning monk when he was 16 years old. Later in life, his followers would call him “Thay,” which is pronounced either “Tay” or “Tie.” (Thay is the Vietnamese word for “teacher.”)

Illustration by Carla Madrigal

Thay studied Buddhist teachings and also world literature, psychology, science, philosophy, and languages. (He would become fluent in seven languages.) Within ten years of becoming a monk, he had started a temple, published several books, and began editing a major Buddhist magazine in Vietnam. What really got people’s attention was the new angle on Buddhism that Thay was teaching; it was a Buddhism that honored the traditional Buddhist practices to cultivate inner peace and yet was also very engaged with the outside world of politics.

By this point, in the 1960s, Buddhism had been a major world religion for more than 2,000 years. Buddhism grew from the life and teachings of a man named Siddhartha Gautama who lived in India about 500 years before Jesus was born. Siddhartha became known as “the Buddha,” or the “enlightened one,” meaning he had discovered great knowledge.

The knowledge that Buddha found and taught is simply that everyone suffers in life. Sometimes this suffering is on a large scale; people experience war, violence, death, and injustice. Sometimes the suffering is on a more personal scale such as feeling jealous of a friend or someone else’s possessions. Wanting more than we have is a very common cause of suffering for almost everyone—kids and adults. And we often believe the lie that getting something new will make us feel happier. But Buddha noticed that the happiness that comes from getting new things does not last. Soon we have a new desire and believe we’ll only be happy if we get that other thing.This cycle of desire for things keeps us attached to our possessions, always wanting more. Nobody is happier in the end because there is always something else to want. All to say, as Buddha knew, getting new things doesn’t make us happy.

There are other very difficult things that happen in life; pets die, friends get into disagreements, teachers and parents misunderstand us, we make mistakes, and more. And those are just the personal hardships everyone faces. Accepting that life can be hard and difficult actually frees us from believing that new things or new situations will make us happy. If we don’t learn that lesson in this life, Buddhists believe that we are reborn in another life to keep learning. This is called reincarnation, and Buddhists believe that this cycle keeps going until we can learn to release our attachments to things and be grateful for small things such as the breath that sustains us every moment of every day.

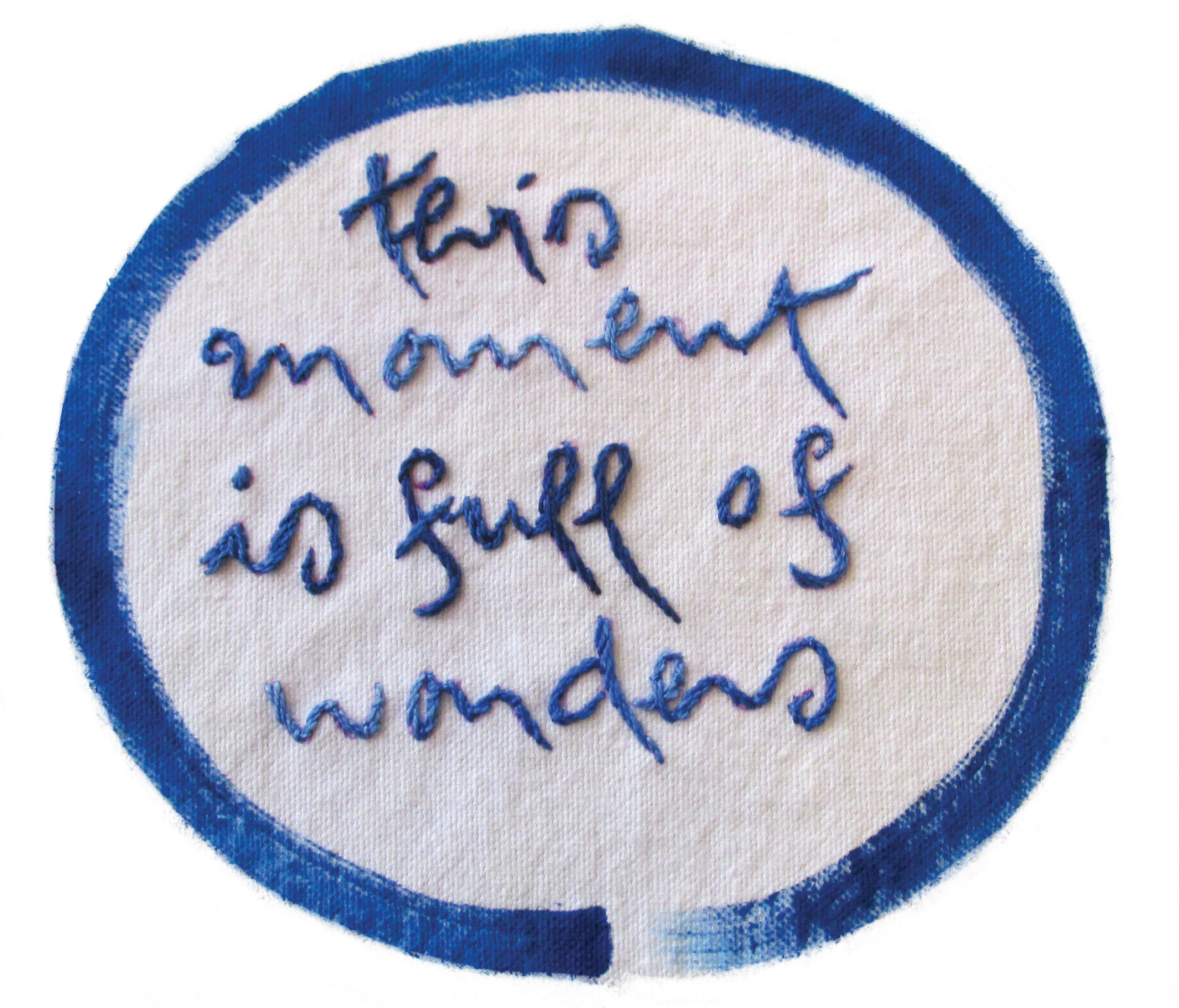

Buddhists encourage us to be aware of the present moment and all that is around us and inside of us, including our own feelings, by meditating. The practice of meditation is as simple as sitting still and becoming aware of breathing in and breathing out. We can pay attention to our inner world. We can notice our feelings without judging them as good or bad. Sometimes we can think of different images such as light and love fill- ing us up every time we breathe in and that light and love gradually spreading to the people and the community around us on every “out” breath. In and out, in and out. As we sit still with our breath, we come back to the present moment. That’s meditation.

Thay not only taught these principles of Buddhism, but he developed a concept which he called “engaged Buddhism.” Buddhism, in the early 1960s in Vietnam usually was personal; Buddhists weren’t very involved in politics or social movements. Thay believed that the practices of Buddhism to develop inner peace and contentment should also benefit the people and community. He wanted to apply Buddhist practices to the real suffering around him. “We wanted to offer a new kind of Buddhism—a Buddhism that could act as a raft, to save the whole country from the desperate situation of conflict, division, and war.”

When Thay was becoming more well known as a teacher, there was a lot of suffering in Vietnam. Many young Buddhists responded to Thay’s call for a new kind of engaged Buddhism. A war was already underway between a Vietnamese group working to make the country independent from the French who had colonized Vietnam in the mid-1800s. In 1965, the U.S. began to get involved in this war, too.

Thay used his growing influence to work for peace for everyone. He founded an organization called Interbeing with several other monks and nuns who also believed in engaged Buddhism. They believed the violence needed to end and believed in a nonviolent process to make social change. They refused to take sides in the war, instead wanting to help anyone who was suffering. They began a magazine called The Sound of the Rising Tide which Thay edited to promote peace and end violence. It quickly became the most popular magazine in Vietnam. Thay wrote many poems in this magazine that were used as protest songs by the Vietnamese people who wanted peace.

Thay’s refusal to take sides upset both of the warring factions in his country. His growing influence made the government nervous. In 1966, Thay was invited to speak at a university in the U.S., and he left Vietnam for a few weeks. “I thought reaching out directly to Americans about the war would be most effective.”

He met with important leaders of nonviolent movements in the U.S., including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Thay and Dr. King quickly realized how much they had in common, even though they were working in such different parts of the world. They both believed in peace and equality. And they both believed in nonviolent methods to achieve their goals. They also believed that other people were not the enemy. Even when other people were doing great harm, the person wasn’t the real enemy; but rather the real enemy was the harmful ideology that made that person believe that his or her only path was violence.

They had a joint press conference, and Dr. King spoke out against America’s growing involvement in the Vietnam War. Dr. King also nominated Thay for the Nobel Peace Prize, which he himself had just won. Dr. King wrote, “I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of this prize than this gentle monk from Vietnam. He is an Apostle of Peace and Nonviolence. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.”

The government in Vietnam was already angry with Thay for not taking their side in the war, and while Thay was visiting the U.S., the leaders in Vietnam decided to exile him. He was banned from returning home, and his country no longer considered him a citizen. Thay was devastated. His closest friends, fellow monks, and co-workers for peace were all back in Vietnam. The temple he had started, which he considered his spiritual home, was in Vietnam. “My entire community was at home,” he later said. “I was like a bee taken out of the beehive.”

Eventually, France granted him asylum, which means the government in France allowed him to live in France and have the same freedoms and rights as a French citizen. He felt grateful for a place to live, but he missed his home.“I dreamed of home almost every night for a year,” he said.

Although he missed his homeland, Thay began working for peace while living in France. He began a Buddhist temple in France, gave lectures, and represented Vietnam in the Paris Peace Talks. Although the Vietnam War ended in 1975, average Vietnamese people were still in danger. Those who had not taken the side of the winning party knew they were not safe, and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese people began fleeing the country. Many of them fled in boats because Vietnam is bordered by the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. These refugees faced major dangers, from leaky boats to untrustworthy captains looking to take advantage of vulnerable people, to pirates. And even when they did make it to shore in another country, often the people in that country didn’t let them live there.

Thay and the friends he’d made in France got to work helping these refugees, called “boat people” because they had escaped Vietnam by sea. Sister Chan Chong was one of his closest friends. She had been one of the nuns who had worked alongside Thay for peace back in Vietnam prior to his exile and came to France to work with him again. Thay started raising money to hire some large freighter boats to rescue a lot of refugees at once. In the meantime, Sister Chan disguised herself as a fisherman in Thailand and went out to sea with food, fuel, medical supplies, and directions to refugee camps. She helped hundreds of people. Thay and Sister Chan’s combined efforts on behalf of the boat people helped raise the profile of all of the Vietnamese refugees. Countries, including the U.S., ultimately admitted many more refugees than usual. About 2 million Vietnamese people left their home country during the crisis that lasted from 1975-1995.

Thay continued teaching the principles of engaged Buddhism in France. So many people came to learn and practice Buddhism with him that he and his followers had to find a larger home. In 1982, they bought a piece of land in southern France and named it Plum Village because plums grew well in the area. Within a few years, Plum Village grew to become the largest Buddhist monastery in the West.

Thay enjoyed living each day with his fellow monks, nuns, and students. Together they worked the soil, cooked, cleaned, and completed all of the chores required to keep a large community running smoothly. In everything, Thay encouraged mindfulness, which is paying attention to what you are doing in the moment you are doing it. If you are eating, he said, pay attention to each bite of food and how it tastes and feels in your mouth. If you are talking to a friend, pay attention to them completely.

Another major teaching of Thay’s is compassion. Buddhists believe in trying not to cause harm. For many Buddhists, including Thay, this means choosing a vegetarian diet. Taking a spider outside of the house instead of killing it or rescuing a worm from the sidewalk after it rains are small acts of compassion that we can engage in every day. And doing small acts of compassion helps train us for larger acts of compassion, like helping refugees fleeing violence or forgiving someone who has hurt you. Living out this practice is what makes a person enlightened. “A Buddha is someone who is enlightened, capable of loving and forgiving,” Thay wrote in True Home, one of the 70 books he published. “You know that at times you’re like that. So enjoy being a Buddha.”

Even when we can enjoy “being a Buddha,” Thay teaches his students that life will still include suffering. That is part of being human just as much as experiencing joy and hope. The question is what do we do in the face of suffering? The answer is to acknowledge our suffering and the suffering of others. “Our response to suffering can bring more suffering, or it can bring some relief and hope,” Thay says.

In 2014, Thay’s health began to decline after he had a stroke. Since then, he has let his students do the teaching. He is content letting his daily life and presence serve as his teaching now. In late 2018, Thay was allowed to return to Vietnam where he expects to live out the rest of his life. Now he sits serenely, just like that picture of the Buddha he was so drawn to as a young boy.

What do you think it means to “be a Buddha”?

Glossary Terms

Activist

A person who works for some kind of social change, from gathering signatures to keep a local library open to marching to protest an unfair law.

Asylum

A temporary refuge and place of safety for people who are escaping warfare, danger, or other hardships in their homelands.

Buddhist/Buddhism

A person who follows the Buddhist religion. Buddhism is based on the teachings of Buddha, who lived more than 2,600 years ago in India. Buddha taught that everyone suffers in life, but that there are ways to become “enlightened” and stop feeling personally oppressed by the loss and pain that occur in life. (See also Engaged Buddhism.)

Colonization

To form a colony or settle in a specific region outside of one’s own homeland, usually displacing Indigenous people from their Ancestral Lands. In the U.S., European colonizers displaced Indigenous Native Americans, most often through violence. Similar colonization happened throughout the world with Europeans taking over resource-rich land in Africa, the Caribbean, South America, Southeast Asia, and more from Indigenous peoples.

Engaged Buddhism

A concept in modern Buddhism, using Buddhist spiritual practices and insights to work to end social injustices; compassion with action; a major teaching of Thich Nhat Hanh.

Equality

The idea that everyone should be treated the same under the law; many social movements are about helping government systems and laws treat all people equally.

Ideology

The beliefs that guide an individual in their thinking about the world and how it should operate.

Meditation/Meditate

Thinking deeply or quietly focusing one’s mind for a period of time for religious or spiritual purposes or to relax.

Mindfulness

An attentive mental state achieved by focusing one’s awareness on the present moment; people can eat mindfully, walk mindfully, play mindfully—it’s about paying attention to where you are right now.

Monks

Members of a religious community, usually never-married men (although there are some female monks, too) who take vows of poverty and obedience; there are Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, and other kinds of monks.

Nobel Peace Prize

A major prize awarded annually for “outstanding contributions in peace;’’ famous recipients include Malala Yousafzai, Barack Obama, and Jimmy Carter.

Nonviolence

The use of peaceful activities, not force or violence, to bring about positive change; the goal is always to help the people currently doing harmful things to see how what they are doing is wrong and change, so people are never seen as the enemy but bad, harmful ideas are the enemy.

Reincarnation

The idea that the spirit or soul of a person lives on in a new physical form after biological death.

Spiritual

Something that relates to the human soul or spirit.

Vietnam War

A 20-year Civil War in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia starting in 1955. It was fought between communist North Vietnam and Southern Vietnam; the North won. (The South was supported by anti-communist countries, mainly the U.S.)

West/Western

The “Western world,” during Roman Antiquity meant Italy and the countries west of it; today it generally refers to places where most people speak European languages such as English, French, and German.

Read another sample chapter from the Holy Troublemakers & Unconventional Saints book by Daneen Akers.